“Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon” captures that bittersweet second before innocence slips away—when love feels urgent, protective, and a little afraid of time.

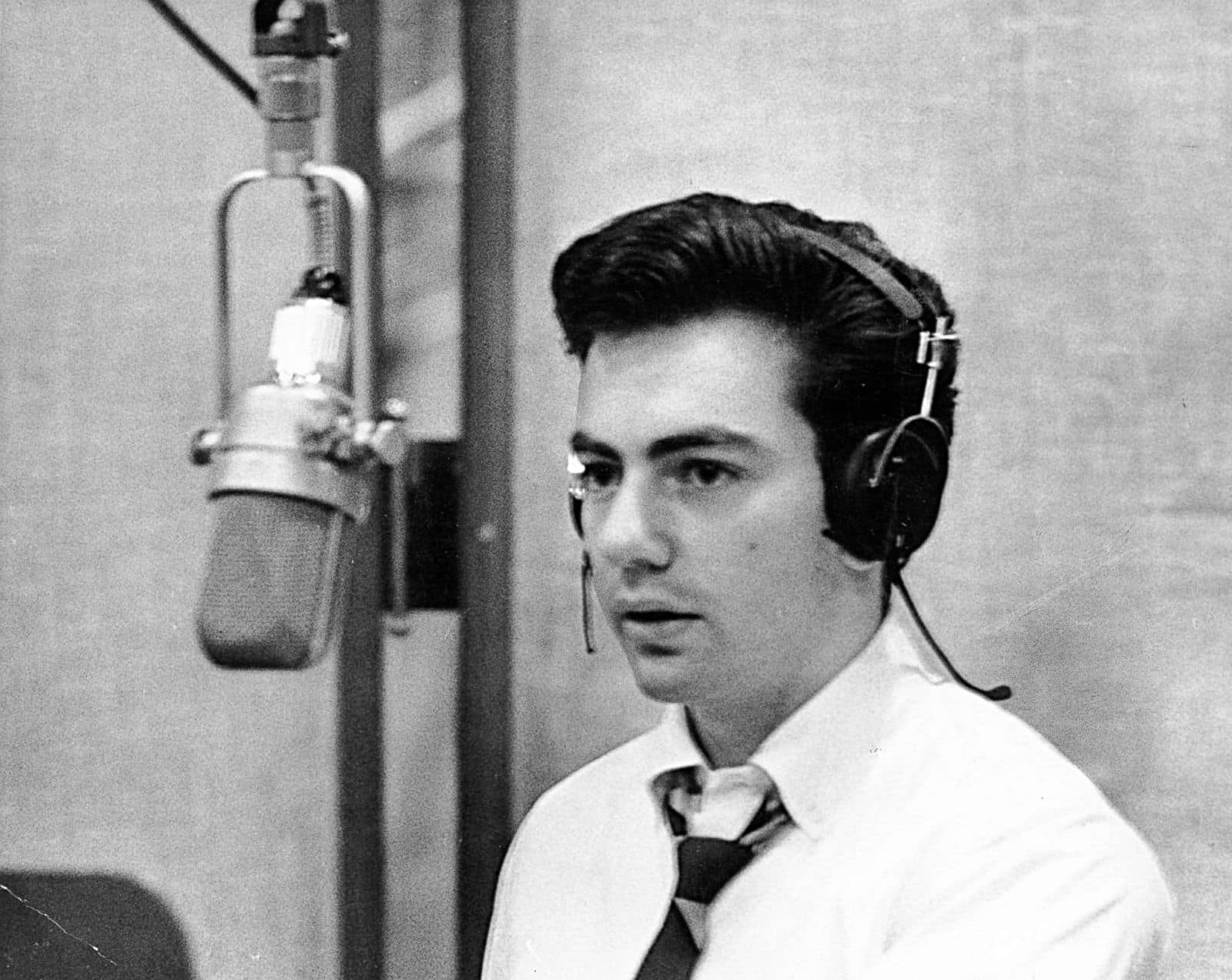

In the spring of 1967, Neil Diamond put a very specific kind of longing on the radio—one that didn’t need grand poetry, just a plain sentence and a trembling certainty behind it. “Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon” arrived as a single on Bang Records, released in March 1967, and it quickly became one of the defining early signatures of Diamond’s songwriting voice: direct, melodic, and emotionally crowded, as if too many feelings were trying to fit into one small room.

The numbers—important, but never the whole story—tell you how far that feeling traveled. Diamond’s recording reached No. 10 on the US Billboard pop singles chart (Hot 100) in 1967. It also appeared on his album Just for You, a record that captured him in that Bang-era sweet spot: half Brill Building craft, half street-corner confession. The single was produced by Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich—a powerhouse pairing whose pop instincts helped frame Diamond’s voice with just the right mix of rhythm and drama.

What makes “Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon” endure isn’t only its chart success; it’s the emotional situation it dares to stage. The narrator is speaking to a young woman poised on the edge of adulthood, and he’s pleading—gently, insistently—for her to choose her own truth over the judgment of friends and family. Diamond writes the opposition as a chorus of disapproval (“they’re not your kind,” “they put me down”), and the song’s heartbeat becomes the tension between outside voices and private desire.

That’s the song’s hidden engine: it isn’t merely a love song, it’s a song about agency—about the frightening moment when someone becomes old enough to decide what love means, and who gets to define it. The title sounds like a compliment, but it also carries a hush of impatience, even possessiveness: soon implies time is running out, that change is coming whether anyone is ready or not. And that complicated mix—tenderness braided with urgency—is precisely why the song still feels alive rather than merely “old.”

Musically, the record balances restraint and release with real craft. It moves as a mid-tempo pop-rock ballad, but it’s staged like a miniature drama: Diamond’s vocal begins almost conversationally, then gradually tightens, as if the words are pulling him forward. Contemporary trade press even predicted strong chart potential—Billboard called it a “sure-fire chart topper” in its single review, praising the rhythmic backing and “soulful” reading. That confidence wasn’t misplaced: the song has the kind of chorus that doesn’t just repeat—it insists, as if repeating the line might make the future arrive safely.

There’s also a fascinating “behind the record” detail that deepens the listening experience: sources note that the mono single/LP and stereo LP mixes differ in when the strings enter and in the fade length—small differences, but they change the emotional lighting, like moving a lamp closer to a face. It’s a reminder of how carefully this era sculpted mood, even inside a two-minute-forty-eight-second pop single.

And then, decades later, the song gained a second cultural life—proof that a strong emotional premise can outlive its original decade. Alternative rock band Urge Overkill recorded it in the early 1990s, and their version became widely known through Pulp Fiction (1994). That cover even charted, reaching No. 59 on the US Billboard Hot 100 and No. 11 on Billboard’s Modern Rock/Alternative Airplay chart, introducing Diamond’s core melody and lyric to a new generation with a very different kind of cool.

Still, the emotional center belongs to Neil Diamond’s original: a young writer-singer capturing the uneasy beauty of transformation—how love can feel like both sanctuary and storm when growing up is unavoidable. “Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon” doesn’t pretend that time is gentle. It simply asks—softly, stubbornly—that when time arrives, the heart won’t be talked out of its own knowing.