“Hurtin’ You Don’t Come Easy” is Neil Diamond’s soft-spoken confession that love can wound—yet it still takes effort to walk away with clean hands.

The first thing to know—because it frames everything else—is that “Hurtin’ You Don’t Come Easy” was never introduced to the public as a headline-grabbing single in its own right. It began life as an album track on Neil Diamond’s fourth studio album, Brother Love’s Travelling Salvation Show, released April 4, 1969. Later in the year, it gained a second, quieter career as the B-side to “Holly Holy,” the Uni single released October 13, 1969. And while a B-side can become legendary in the hearts of listeners, it usually does not receive an official “debut chart position” of its own—its spotlight is borrowed from the A-side.

That borrowed spotlight, in this case, was bright. “Holly Holy” entered the Billboard Hot 100 in the week of November 1, 1969, debuting at No. 71, and later rose to a No. 6 peak (also reaching No. 5 on Billboard’s Easy Listening/Adult Contemporary chart). Even the Cash Box chart captured its early arrival: on October 25, 1969, “Holly Holy” appeared at No. 74 in its first week on that ranking. So, if there is a “moment of arrival” attached to “Hurtin’ You Don’t Come Easy,” it is this: it rode into living rooms and car radios on the reverse side of a major late-1969 hit.

But the deeper truth of “Hurtin’ You Don’t Come Easy” belongs to the album that first held it. Brother Love’s Travelling Salvation Show was recorded across 1968–69, and its production credits read like a crossroads of Diamond’s early Uni-era sound: Tom Catalano, Chips Moman, Tommy Cogbill, and Neil Diamond himself. Those names matter, not as trivia, but because they suggest a working atmosphere where polish and spontaneity could share the same room. The record carries that feeling—songs that sometimes move like sketches, sometimes land like lived-in stories. And tucked near the end of side two sits “Hurtin’ You Don’t Come Easy,” modest in length, almost modest in posture, yet emotionally unmistakable.

Its meaning is written right into the title: hurting someone is not always a dramatic act. Sometimes it is the slow, reluctant consequence of choosing oneself, or admitting what the heart can’t keep pretending. The song doesn’t sound like a man trying to win an argument; it sounds like a man trying to keep his conscience from turning into a permanent bruise. That’s the special ache here—pain with moral weight. The narrator is not only wounded; he’s aware that love makes him responsible, even when love is failing.

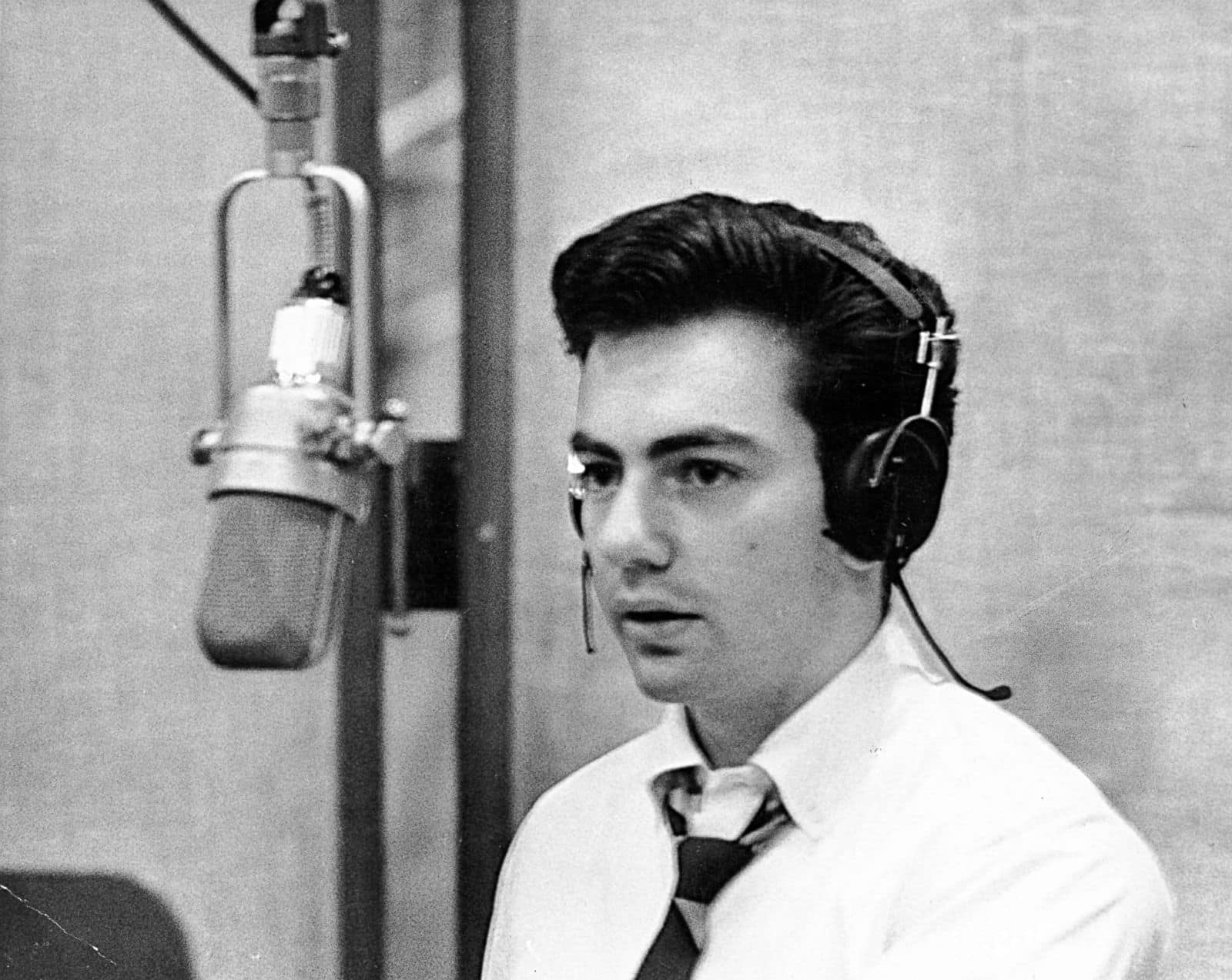

Musically and emotionally, Neil Diamond keeps it close to the chest. There’s a plainspoken, almost conversational quality to his delivery—one of those performances where the phrasing feels like it’s following thought itself, as if each line is decided in the moment it’s sung. It’s not a song that begs for applause; it asks for recognition. It names a feeling many people avoid saying out loud: that ending something can be necessary, and still feel like sin.

And maybe that’s why the track has endured as a kind of quiet companion piece to the larger hits around it. “Holly Holy” reached upward with gospel-colored grandeur and public celebration. “Hurtin’ You Don’t Come Easy” moves in the opposite direction—down into the private room, the dim lamp, the pause between words. It doesn’t chase immortality. It accepts memory. And in that acceptance, it becomes