“Until It’s Time for You to Go” is Neil Diamond singing the bittersweet courage of loving someone you can’t keep—choosing the truth of now over the fantasy of forever.

In early 1970, Neil Diamond released “Until It’s Time for You to Go” as a Uni Records single (UNI 55204), pairing it with “And the Singer Sings His Song.” Its chart life began quietly but unmistakably: the record debuted at No. 87 on the Billboard Hot 100 on February 21, 1970, then climbed to a peak of No. 53 (with its peak week shown as early March). On Billboard’s Adult Contemporary/Easy Listening chart, it rose higher in spirit than in noise, reaching No. 11—a home that suited its mature, evening-lit ache.

What makes this recording feel so poignant is that it is not “a Neil Diamond song” in the usual authorial sense. Buffy Sainte-Marie wrote “Until It’s Time for You to Go” in 1965, first releasing it on her album Many a Mile. She described it as arriving in her mind while she was falling in love with someone she knew could not stay with her—an origin story that already carries that particular kind of tenderness: the heart stepping forward even as the mind holds the door half-closed. The lyric’s situation is simple and devastating: two people love each other, yet “come from different worlds,” and the only honest request left is not a promise, but a permission—don’t ask forever; love me now.

Diamond’s version was tied to his album Touching You, Touching Me, released November 14, 1969 on Uni. Even the album title sounds like the emotional logic of the song: closeness that is real, immediate, almost physical—yet always threatened by time’s inevitable pull. The album itself peaked at No. 30 on the Billboard album chart and was certified Gold, a reminder that this period of Diamond’s career balanced commercial momentum with a growing willingness to interpret other writers’ material when the emotional fit was undeniable.

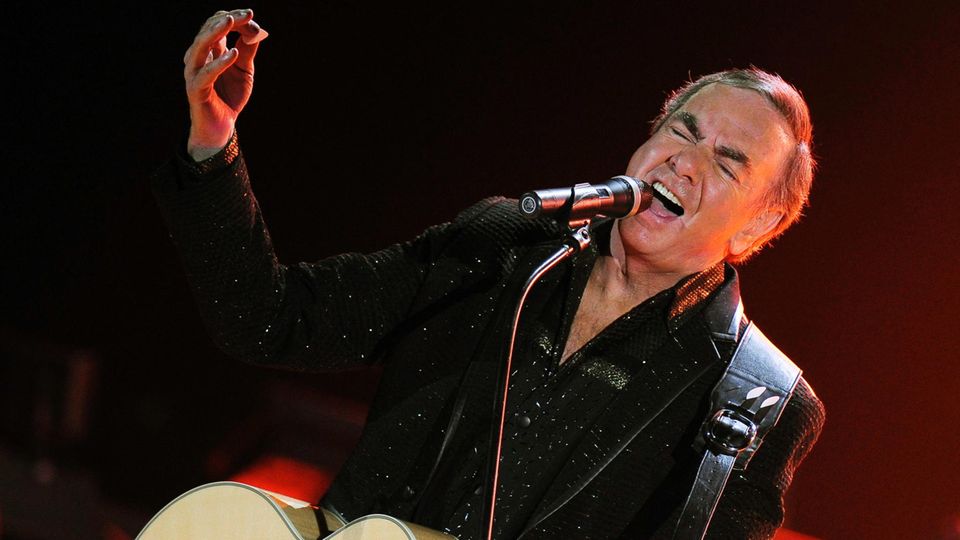

And the fit here is extraordinary. Diamond doesn’t sing “Until It’s Time for You to Go” as a dramatic farewell; he sings it like a private agreement spoken softly, so it won’t break. There’s dignity in that restraint. Many heartbreak songs beg to be remembered; this one only asks to be understood. It recognizes that some loves are not defeated by lack of feeling, but by the weight of circumstance—family, culture, distance, timing, the invisible borders people carry inside them. It is an adult kind of sorrow, the kind that doesn’t shout because shouting wouldn’t change anything.

What’s especially moving is how Diamond’s interpretation stands at the meeting point of romance and realism. In his hands, the song becomes less about a single doomed affair and more about a universal moment: the instant you realize that love can be true and still not be permanent. That paradox—truth without permanence—used to frighten people into pretending. This song refuses the pretense. It does not demand the future to justify the present. It treats the present as holy enough.

Contemporary trade reviews noticed the craft of his performance. The song’s later documentation preserves that Billboard praised it as “one gem of a performance,” and Cash Box admired Diamond’s “splendid reading,” noting how his then-recent hits had sharpened and polished his style. Those reactions matter because they explain why the record lingers even without a towering chart peak: Diamond found the song’s emotional temperature and held it steady—never oversinging, never winking, simply letting the lyric stand in its own truth.

If you listen to “Until It’s Time for You to Go” today, what remains is its quiet bravery. It does not promise that love will win; it promises only that love is real—real enough to be chosen honestly, even when it must be released. And that is why Neil Diamond—a singer so often associated with grand declarations—sounds so affecting here: because the declaration is small, almost whispered, and therefore believable.