A Toast to Heartache: The Bittersweet Solace of “Red, Red Wine”

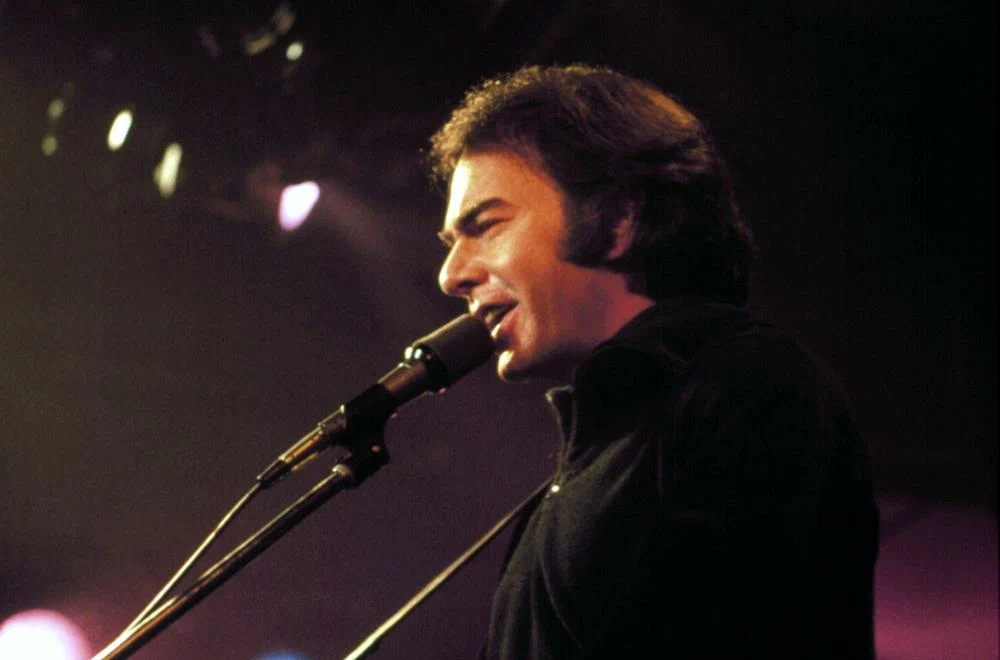

When Neil Diamond released “Red, Red Wine” in 1967 as part of his second studio album, Just for You, the song quietly slipped into the American pop landscape—modest in its initial chart impact, yet destined for a long and unpredictable life beyond its first incarnation. While it reached only the lower rungs of the U.S. charts at the time, its melancholy charm would later find new voice through others—most famously in UB40’s reggae reinterpretation more than a decade later. But before that transformation, Diamond’s original recording stood as a quintessential piece of late‑sixties pop melancholia: simple in construction, aching in sentiment, and unmistakably stamped with his gift for turning private sorrow into universal confession.

At its heart, “Red, Red Wine” is less a drinking song than a prayer whispered into a half‑empty glass—a lament disguised as an easy melody. Diamond wrote it himself, capturing that liminal moment when grief no longer shouts but instead murmurs in resignation. His lyrics do not plead for reconciliation; they acknowledge defeat. The wine is not celebration but anesthesia, a means to quiet the echo of love lost. The track’s gentle pulse and restrained instrumentation reflect that emotional fatigue—the rhythm of someone who has cried all night and now simply wishes to feel nothing at all.

In those early years of his career, Diamond had already begun refining his ability to merge emotional vulnerability with pop accessibility. Just for You, released during his tenure with Bang Records, gathered songs that were deceptively straightforward on the surface yet carried an undercurrent of existential weariness. “Red, Red Wine,” sitting among tracks like “Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon,” revealed a young songwriter who understood that heartbreak rarely ends with dramatic closure—it lingers, dissolving slowly like sugar in dark liquid. His delivery is plainspoken but utterly human; one can almost picture him alone in a dim apartment, staring at the rim of his glass as if it holds the answer to some private riddle.

Musically, the piece leans on an unadorned arrangement—gentle guitar strums, steady rhythm section, and Diamond’s warm baritone floating above it all. This restraint gives the song its potency: emotion distilled rather than diluted. There is no orchestral sweep or pop bombast here; instead, there is intimacy. Each note feels weighed down by memory. In this way, “Red, Red Wine” achieves what so many heartbreak songs attempt but few sustain—it turns sentimentality into something dignified and timeless.

Over the decades, the song’s endurance speaks to its emotional honesty. Listeners return to it not for spectacle but for recognition—for that rare musical moment when vulnerability becomes strength. Before covers turned it into a global sing‑along, Neil Diamond’s “Red, Red Wine” existed as something smaller yet perhaps more profound: a quiet masterpiece about surrendering to sorrow and finding a fragile peace at the bottom of the glass. It remains one of those songs that linger long after the final chord fades—a reminder that even in despair, there is beauty in how we cope, how we remember, and how we learn to let go.